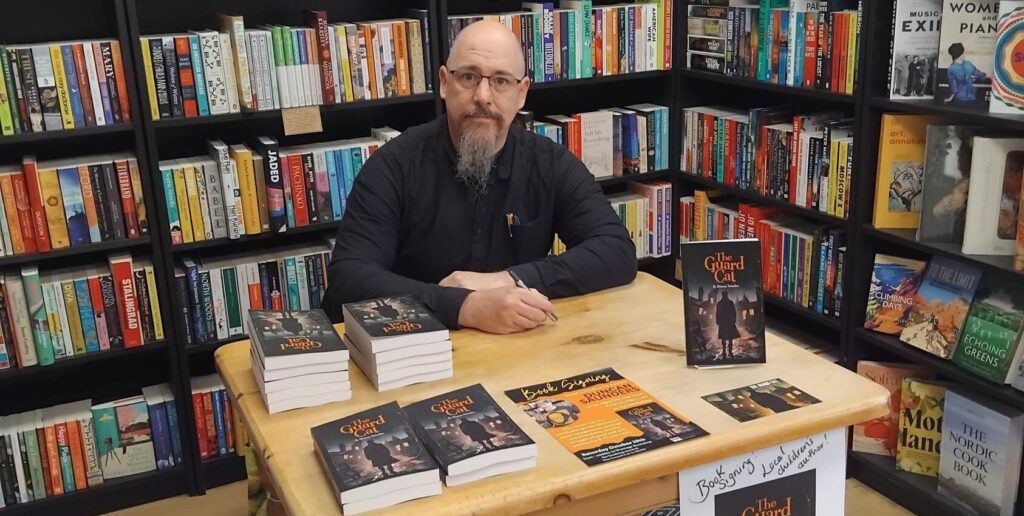

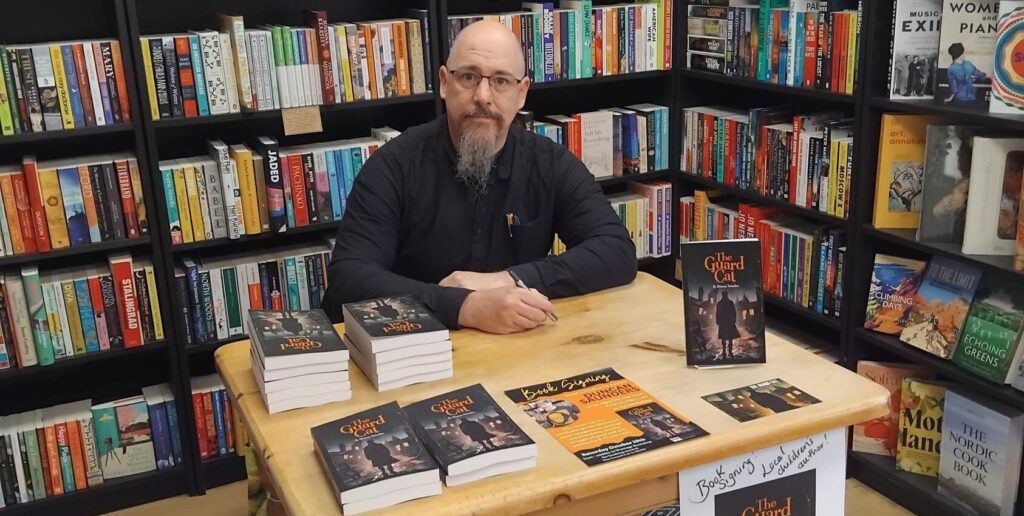

Q&A: Duncan Saunders on his popular Young Adult “horror” novel ‘The Guard Cat.’ Q: It’s been almost a year since the release of The Guard Cat. How has post publication life treated you? It’s been busy. I’ve been involved in several events, signing copies of The Guard Cat, alongside my day job of teaching. Christmas has been my first break since the summer, when the publicity drive for The Guard Cat started in earnest. It’s been busy but enjoyable. Q: How would you describe The Guard Cat? What can readers expect from this story? I describe it as a supernatural adventure novel, set at Christmas in a small English village in the 1980s. It is a story full of mystery, and without giving away spoilers, cat lovers should find plenty to enjoy in the book. It’s ideal for children and young adults (and older adults) who enjoy an eerie, wintery tale. It’s the sort of book that is best read while curled up under a blanket in a comfy chair while the wind howls outside in the darkness of a winter night. Q: Writers have plenty of ideas and fragments of ideas, but not everything, “makes the cut.” What was it about The Guard Cat that persuaded you to put the blood, sweat and tears into its creation? When I was a child, we were snowed into the village where we lived a week before Christmas, during a power cut; I remember making toast over an open fire using a toasting fork and reading by candlelight. It was an experience which stuck with me and later on, led me to think “what if it wasn’t just a storm?” The story then took on a life of its own. I hope I’ve done justice to the dark and creepy atmosphere of that midwinter in the countryside. Q: Did you read much horror or weird fiction as a kid? Who were your favourite authors when you were 13 or 14? I was a voracious reader as a youngster. At 14, I’d graduated from Roald Dahl onto fantasy fiction; I’d discovered Tolkien by that time and had read a few Terry Pratchett books. I think I was reading the Dragonlance trilogy. A year or two later I discovered darker stories by authors such as Stephen King, so my love of the supernatural came a little later and it wasn’t until my twenties that I started reading more of the classic horror writers, such as Lovecraft. Q: Is it true you used to be a professional wrestler? It is; I think some of the matches can still be found online if you know where to look! I wrestled for a few years, mostly in the South West of England. I was a filthy villain called The Gallowman, who would cheat to win and used a hangman’s rope in his matches as often as he could get away with it. The storytelling and character aspect of wrestling always appealed to me; my wrestling days may be in the past, but The Gallowman as a character may one day make a reappearance. Q: Do you have a particular daily routine for your writing? What are some of the enjoyable, hardest, and strangest parts about writing for you? Being a teacher as my “day hustle” can make it a struggle when it comes to writing; my usual time is the last few hours of the day, before bed. This can be a problem if I get on a roll, as I’ll keep going and suddenly realise that it’s 3am! I absolutely love bringing characters and stories to life and hearing that someone has enjoyed something I’ve written is a huge compliment and the best feeling that there is. Q: What or whom have been the biggest influences on your writing? As mentioned previously, I love fantasy fiction; Tolkien, Terry Pratchett and later authors such as Tad Williams have all influenced my love of reading if not my writing style. The Guard Cat was influenced by classic horror such as Dracula and the works of HP Lovecraft, although it feels arrogant to mention myself in the same breath as such greats. As for my writing, I’d describe my ideas process as looking out of the window, asking “What if?” and then developing the ideas. Q: What advice would you give to other aspiring writers? Firstly, keep writing; like any skill, the more you practise, the better you get. The other thing that has helped me is to listen to all the advice you can get from people who have been there before, and then choose the parts that suit you. Everyone’s voice is unique, so use what you can to help you find yours. Q: What’s next for you? Do you intend to continue writing YA fiction? Absolutely; I’ve heard it said that a writer isn’t someone who chooses to write, it’s someone who can’t stop themselves writing. More specifically, a follow up for The Guard Cat is on its way. Watch this space for more details! BUY THE BOOK A wonderful gothic adventure about imagination, courage and friendship and the struggle of good and evil. In a small English village, cut off from the outside world during a snowstorm and blackout a few days before Christmas, something wicked is threatening life as they know it.. A trio of unlikely heroes ~ members of an elite organisation known as The Order of the Silver Shield ~ come to the rescue of the endangered inhabitants. Standing in their way is a dreadful life draining entity called The Unbeing and the cunning Dr Von Hawkfire. Will The Order of the Silver Shield be a match for the diabolic duo, or will darkness prevail? Genre: Fantasy/Young Adult fictionFormat: 232 pages, PaperbackISBN: 9781739394974 Add to Cart ABOUT THE AUTHOR DUNCAN SAUNDERS is a teacher and former professional wrestler whose first novel, Dinosaurs, Aliens and The Shop That Sells Everything (Ghostly Publishing) featured on the Amazon best sellers list for Children’s Sci-Fi. He lives in the shadow of the Uffington White Horse in Oxfordshire. His literary influences include Roald Dahl,

A Q&A with crime novelist Samantha Turner who discusses her book The Burning Truth, a gripping drama surrounding the discovery of a body in a locked, burning canal boat – the latest instalment in the Lizzie Holland crime series. What first inspired you to write The Burning Truth? The Burning Truth carries on the back story started in my first two novels, The Devil You Know & The Depths Of Murder which follow the protagonist, Lizzie Holland and the tragedies that befall her. The inspiration for the novel came from wanting to provide answers to the ongoing mystery as well as highlighting the struggle between Lizzie’s crucial role as a DI and her turbulent personal life. I have a close relationship with the canal as I can see the towpath and water from my patio. Seeing the array of colourful (in appearance and name) of the various barges sailing by and the houseboats that are permanently moored here, the story for The Burning Truth began to form in my imagination. Combined with the location of my local pub and other areas I have visited plus, a sprinkling of artistic licence the novel was brought to life. Themes of gender and violence pervade the novel. What inspired this decision? I find this question a little difficult to answer as I didn’t begin with this intention; I never do! The story develops a life of its own as I hit the keys. However, I am a writer of crime thrillers so my readers do expect some level of violence. As for gender, again I didn’t give it much thought. Violent crime can happen to anyone, and yes, we seem to hear more on the news about violence against women, but I feel we shouldn’t discount the risk to men. Whatever our gender, high-risk lifestyles, deciding to take that shortcut down the dark alleyway, or just being in the wrong place at the wrong time all have the chance of ending in tragedy. How would you introduce Lizzie Holland to your readers? The Lizzie Holland we see now is quite changed to the despondent, negative woman from book one. Lizzie is a fiercely strong and independent Detective Inspector, at almost fifty years old she has only been part of The Lancashire Constabulary for ten years. Solving violent murders, rapes and other vicious incidents in the Major Crime Unit is her new purpose for living. Sometimes her need for justice can give way to vengeance if she allows her temper and past experiences to overcome her judgement. In her spare time, the once unfit and overweight Lizzie likes to run, practice self-defence and drink lots of strong coffee. She is also an avid animal lover and vegan. What research did you do in the writing process? I am fortunate to have an acquaintance who owns a canal barge and one who lived on a boat for many years. My other friend is an ex-police officer. I am afraid to say I bombarded them all with questions and I had the opportunity to view the barge in person which gave me a good insight into the layout etc. I also spoke with my local fire brigade and used my past career as a pharmacy technician for accuracy. While some of the locations in the book are based on real places which I visited I have invented certain names, pubs, and landmarks for the good of the story. What do you hope readers will take away from this novel? Firstly, I hope readers will thoroughly enjoy the novel. I also wish for readers to invest in Lizzie Holland, to care about what happens to her and to walk by her side. If the novel stirs emotions, creates suspense and instils fear then I have done my job. However, I have added a touch of humour for light relief. The novel hits on controversial topics, I hope readers aren’t offended by this and understand that as authors we have to portray all opinions, even if they seem cruel or out of date. The Burning Truth by Samantha Turner is published by Foreshore in the spring in paperback. SAMANTHA TURNER is an English crime writer, novelist and poet. She is the creator of the Lizzie Holland series and author of The Devil You Know and The Depths of Murder – the first two Lizzie Holland crime novels.

People’s Book Prize Award winner finalist Dr Sarah Hussain takes questions from Foreshore Book Club Members across the UK. I know you were at Huddersfield University, so did this novel start there, or pre-date that time, and can you remember what the seed of this was, as a novel? HENRY, London Yes, the novel was inspired by my PhD research. I came across the amazing hill women of the Himalayas who protested to protect the trees. Having come across so many stereotypical depictions of South Asian women, I knew the best way to challenge such negative representations was to write a novel and pay homage to these unsung female activists. I was inspired by their non-violent activism and new I had to tell this story. What is the role of isolation in your creative process? IH, Birmingham I am inspired by nature. Going for walks alone helps my writing come alive. Before writing the trek section of my novel, I would go on regular walks in the woods, using my phone to record my thoughts; I would make note of the small details in relation to sight, scent and sound. When you had completed your novella Escaped from Syria, did you know at that point that you would be writing Vidhya’s story in your next novel? YF, London No. I knew I wanted to write about British/Indian connections from a postcolonial perspective, but I was inspired to write Vidhya’s story when I learnt about environmental colonialism and the hill women’s contribution to India’s independent struggle. I love how the novel manages to explore its socio-economic and political context while avoiding judgement or easy conclusions, even though it’s written from Vidhya’s point of view. Was this a hard thing to balance? EB, London Yes, it was difficult. Initially I was so engrossed in my research that I had to be really careful not to just info drop. I had to remind myself that this was a story that required me to draw on the real life lived experience of the indigenous people. There are already academic books written about the colonial period in India, but I struggled to find fiction written about the British Raj era from the native Indian’s woman’s perspective. My intention was to try and create a plausible setting that would paint a picture of the real-world Vidhya lived in, so this meant focusing on her experience within the socio-economic, political and environmental context. How did you go about creating and inhabiting an Indian teenager (Vidhya )from a different century, giving her such truth and feminist autonomy? GEMMA, Christchurch, Dorset I know it’s a different century, but as a South Asian woman, I understand what it means to grow up within that culture. My South Asian heritage means a great deal to me. Although I am British born, I hold on firmly to my ancestral values, thus I felt creating Vidhya was a very natural process. It might sound unusual, but once her character was born, I felt as though she guided me, more than her being my creation. Writers create literature, shape it, but how to be unique in that art of creating some new styles of historic fiction writing? DARLENE, Brighton My PhD research was about contributing to new knowledge, thus my intention to challenge romanticized depictions of South Asian women was a new contribution to English fiction within the British Raj era. I think the way to be unique is to write a story that challenges what people think they know about a historical period. In terms of style, I believe each writer develops their own voice that has its own unique style. I have often been advised to take inspiration from other great writers which is good advice, but it’s also great to take risks. I myself prefer a plot driven novel and I’m not a fan of purple prose, but a lot of novels I read which were set in that part of the subcontinent were heavy in description. I wondered whether I needed to conform to that style of writing, however it didn’t work for me. I wanted to write a historical novel that made readers want to turn the page and find out what will happen next, as well as learning about a period in history that they never knew about. I hope I have achieved that. Is there a book by another author that you would love to have written yourself and, if so, which and why? VERONICA, Belfast I believe every individual has their own voice, so I wouldn’t want to have written any other story that I wasn’t inspired to write myself, but I have certainly enjoyed other fiction. My love for fiction began when I read Alice Walker’s, The Colour Purple. Walker created a plausible setting that took me on an emotional journey and the best books for me are the ones that move you and make you question the world. Which do you find most challenging writing a thesis or a novel? BRIANNA, Conway The novel by far was the most challenging. I discovered this new knowledge and was eager to complete my exegesis, thus writing down my ideas including source support was not that difficult for me, especially since I have taught Academic English skills. However the novel was like building a house from scratch; getting the structure in place, before decorating and adding the final touches. I had to get the plot right within a specific historical time frame, which took some redrafting, whilst ensuring there weren’t any anachronisms. Once I managed to create a plausible plot, then I had to consider writing style and this meant word level editing, which is a lot more strenuous than writing an academic thesis in my opinion. Creating Writing is very technical and writing a historical fiction novel was most certainly a challenge, but I am very proud of taking on that challenge and writing a novel that contributes to new knowledge. BUY THE BOOK A powerful