Double Dutch

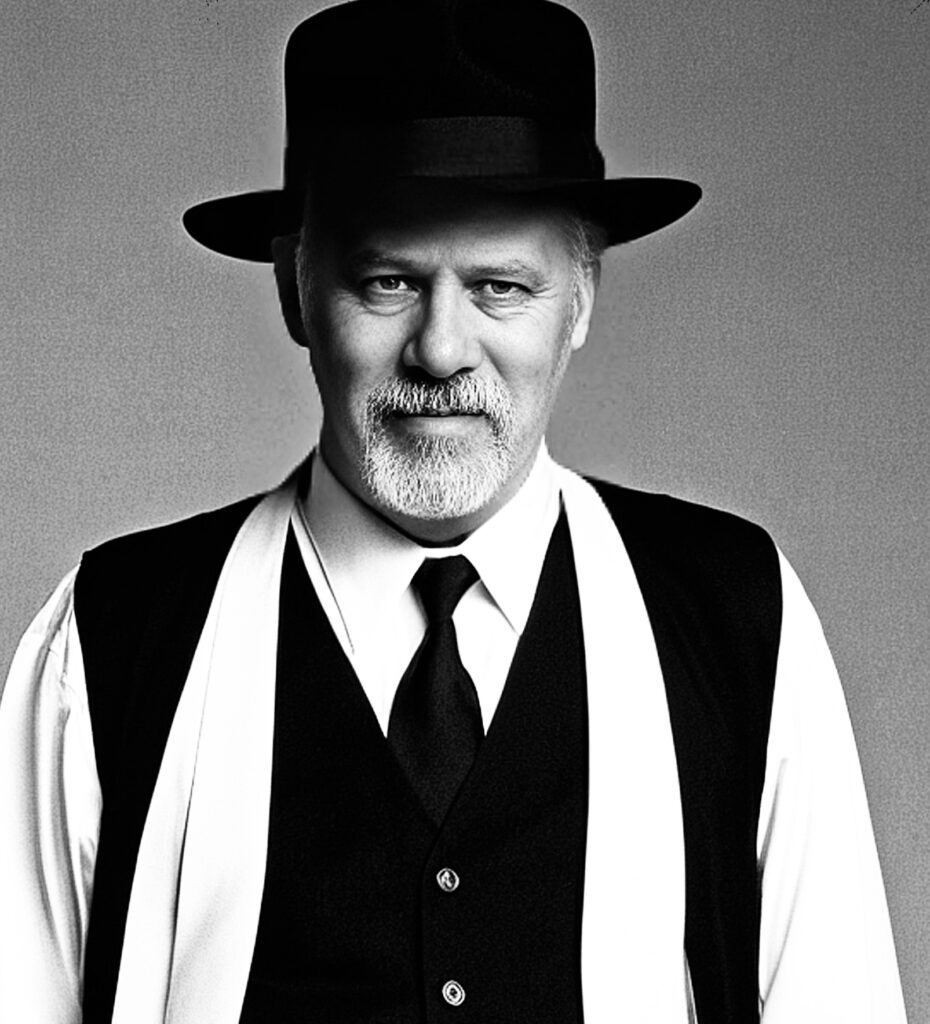

The Inbetweeners meets Lock Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, D.R. Fenner and Jacqueline Haigh’s debut comedy crime is based on true events and the Dutch crime duo Johannes Mieremet and Sam Klepper. An accountant at a successful London bank and his two best mates throw themselves into an Amsterdam adventure – but their antics disrupt the lives of the city’s two most notorious gangsters; Spic and Span are named after the ruthlessly efficient means taken to dispose of their victims. ‘Some tourists think Amsterdam is a city of sin, but in truth, it is a city of freedom. And in freedom, most people find sin.’ Sweat beaded on Ando’s forehead then meandered down his cheeks in rivulets. The cold muzzle of the gun pushed against his left temple so hard it hurt. Holding the weapon was a neatly suited, clean-shaven Dutchman with greased-back, dark brown hair. His shark-like eyes glistened. Meanwhile, his accomplice, a heavy-set guy with a pugnacious face, stood across the room grinning. Spic and Span never sent henchmen to do their dirty work. They viewed this as their vocation – it wasn’t just about making money. It was a matter of reputation. ‘Well now,’ the gunman said, waving his pistol calmly. ‘That’s interesting because my good friend Mr Beretta here says you’ll do exactly as you’re told.’ Span stretched up to his full height of six foot three. Ando looked across the room, to where his friend, Dickie stared in horror at the second gangster, who was even taller, and roughly the same distance across the shoulders. An archetypal hatchet man, he looked the type you could run over with a tank, and he’d get up and smile at you. Dickie was squirming, hunched in his chair in a way which accentuated his double chin. Ando knew that expression only too well. Dickie was doing the face he always did when trying not to soil his pants, which he would no doubt blame on his gastric issues if they got out of here alive. Dickie’s wide-eyed countenance caught the attention of Spic, whose forehead creased into a frown. ‘You like me, pretty boy?’ He sneered. ‘Should I bend you over and make you my bitch?’ ‘Err… no,’ quivered Dickie. ‘Then stop eyeing me up.’ Dickie lowered his eyes and fixed them on the gangster’s shiny, wing-tip shoes. Ando glanced over at his other friend, Hoppa, hovering further to his right. Strangely, despite the fraught situation, Hoppa looked relaxed, almost a smirking. How does he do that? Ando thought. No wonder he’s so good at poker. Over the years, Ando had heard about the colourful characters that Hoppa knew, so it was unlikely to be the first time he’d seen someone threatened with a gun. But even so… Unfortunately, the gangster holding the gun to Ando’s head was not so impressed by Hoppa’s laid-back manner. ‘Is something funny, clever boy?’ ‘No, no, nothing.’ Hoppa kept a straight face. ‘You think I’m comical?’ Span yelled. ‘You think I’m a fucking clown?’ ‘No,’ Hoppa persisted. God, he’s good, Ando thought. But, of course, it was a red rag to the Dutch bull. ‘You think you English can fuck with me?’ Span turned and away from Ando, spraying saliva in Hoppa’s direction as he spoke. ‘No.’ ‘Smile again, and I shoot your dick off. Got it?’ Span aimed his handgun at Hoppa’s groin, then twisted his neck, making it crack. His eyes became even more sadistic. Spic was terrifying, but Span took it to another level. He liked to get in people’s heads, to hear them scream. The things Spic had watched his comrade do would make most grown men weep. ‘Please, guys,’ Ando pleaded. ‘We’re not trying to fuck with you. This was all a stupid mistake.’ Span turned back towards Ando, removed a silencer from his pocket and screwed it onto the end of his gun. Ando’s imagination kicked into overdrive. He pictured the bullet exploding through his skull and exiting behind his right ear, scattering shards of bone into the cerebral cortex, back toward the basal ganglia, and down into the thalamus as his brains blew out all over the wall. Over-analysis even at a time like this. He thought. As the tip of the pistol pressed back on his sweaty forehead, a strange sensation flooded over him. Time slowed. The commotion around him faded away. Out of the corner of his eye, he caught a last glimpse of his two best mates as they looked on in horror. ‘You know,’ Span said, ‘some religions think dying is like being born. I like that. An ending, a new beginning, who knows?’ ‘I’m not religious!’ Ando blurted. His voice was shrill. He didn’t know where the words had come from. It was as if they just erupted from his mouth. ‘That’s OK,’ Span said, smiling softly. ‘Just pick a God and pray.’ Behind his closed eyes, Ando heard the sound of the weapon being cocked and waited for his moment. Would it hurt? Would he feel it? He never thought that his time on Earth would end like this, in a soulless hotel room in Amsterdam… This is an edited extract from Double Dutch set for publication with the RiverRun imprint of Foreshore in summer 2025. D.R. FENNER is a novelist who lives with his wife and three young children on the northern beaches in Sydney. JACQUELINE HAIGH is a scriptwriter, story consultant and performer. She has over twenty years of experience as a writer and stand-up comic and has written books and scripts for film, TV, stage and radio. Feature graphic by Eliezer Muller on Unsplash